It happened in Tours at the time of the French Revolution: a political prisoner’s wife disguised herself as a man in order to penetrate the prison where he was being held by the Jacobins, and was clever enough to gain the confidence of the jailer and free her loved one. The episode had a sensational impact on contemporary hearts and minds at the end of the 18th century. One of the witnesses of the event, Jean-Nicolas Bouilly, turned it into a libretto, which was set to music by Pierre Gavenaux in an opera that was premiered in Paris in 1798. A few years later Ferdinando Paër used the same libretto for his Leonora ossia L’amor coniugale, which was performed with great success from 1804 onwards, initially in Dresden and then also in Vienna.

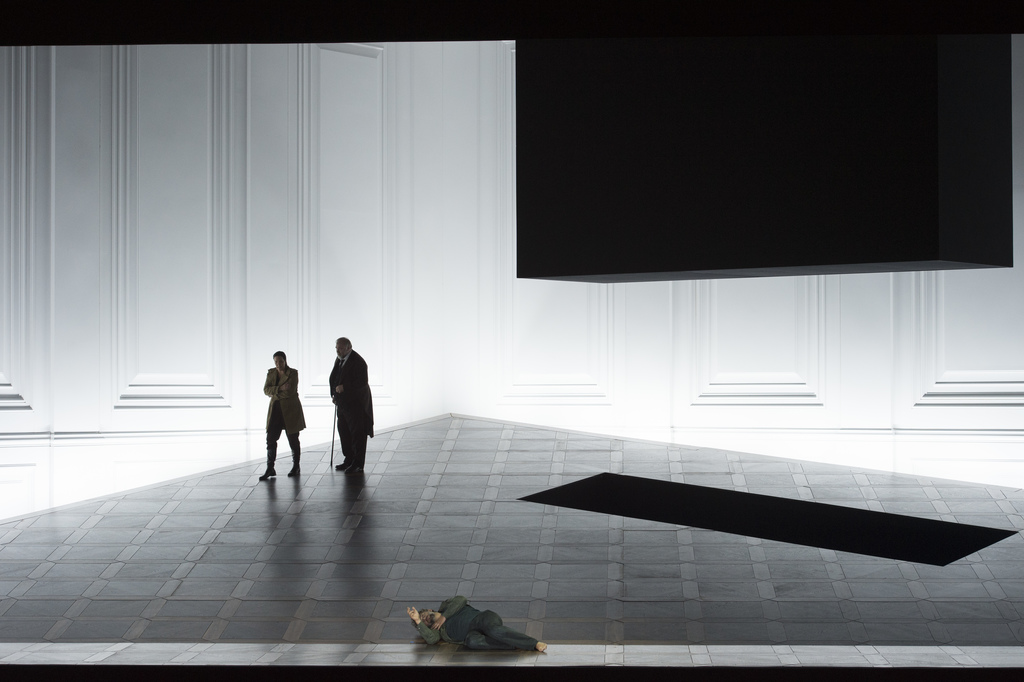

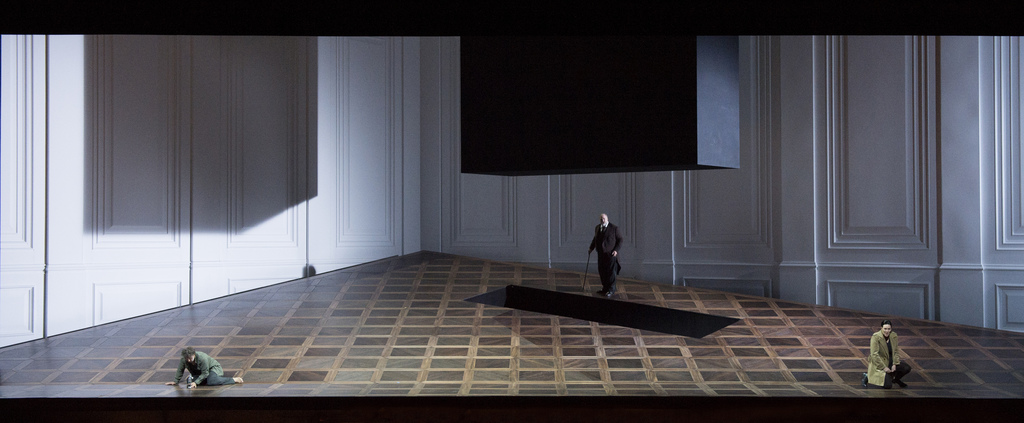

Around that time Beethoven’s living quarters were at the Theater an der Wien, where he was engaged under contract and worked on an opera entitled Vestas Feuer (Vesta’s Fire) to a libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder. Although Beethoven with his classical ideals was fundamentally attracted by the work, he eventually lost interest in it and in its stead had the then director of the theatre Joseph Sonnleithner provide him with a German translation of Bouilly’s Léonore, which contained precisely those elements of moral edification and spiritual exaltation that he as a composer sought in a libretto and which also appealed to him in simply human terms. Beethoven’s Leonore, the first sketches for which coincided with the composition of the Eroica, starts with a first act set in the petit bourgeois world of the jailer Rocco, continues with a second act dominated by the governor of the state prison, and culminates in a third act devoted to the celebration of the triumph of conjugal love over despotism.

However, this plea for humanity and justice dressed up in the guise of a ‘liberation and rescue opera’ was not a success, and it was not until 1814, after ten years of intensive work, that the version was premiered which has become famous as the very epitome of the ‘rescue opera’: Fidelio. As well as concentrating three acts into two, Beethoven also broke down the barriers between the original version’s three distinct spheres: in Fidelio, the desire for happiness may be motivated by egoism but it knows no differences of social standing. The singspiel-like opening of Act One combines with the contemplative quartet ‘Mir ist so wunderbar’ and the famous Prisoners’ Chorus ‘O welche Lust’ to strike a chord that evokes a true utopia, which Beethoven realizes in a blissful but all too brief moment. In the music to which Leonore takes off Florestan’s chains, utopia and reality are made one to the words ‘O Gott, welch ein Augenblick’ (‘O God, what a moment’) before they are swept away in a final breakneck frenzy of joy and celebration. The philosopher Ernst Bloch put it as follows: ‘Nowhere else is music such a bright dawn as here, militantly religious and heralding a day that is already audible as more than just a hope. This is music with the glow of the truly human, unlike anything that Beethoven’s whole cultural world […] had ever brought forth before.’